Membership in the Nazi Party: Is that OK, Father?

When thinking of the reason why the German Catholic Church thought it proper to lift the ban on membership in the Nazi Party in 1933 one needs to think of what the church stands for. If the church felt that the Nazi ideals were not compatible with Catholic ideals, as was the stated reason for the ban, then one needs to think of what changed that prompted the lift of the ban. I don’t think that the church was simply lifting the ban to protect democracy, as some church apologists claim. The church was never interested in protecting democracy. Cardinal Pacelli, then the Vatican Secretary of State and later Pope Pius XII, had no qualms in prompting the disbanding of the powerful Catholic Center Party in Germany, who could have stood up and made a difference against the Nazis. But even if the church cared about democracy, it would not have lifted the ban unless it thought that it was the right thing to do. Imagine today that the Ku Klux Klan became an official political party in the United States, and began to have traction on a platform based on discrimination against Jews, blacks, gays, or anything else. What would the church advise the faithful to do? Would they support the KKK for the sake of supporting democracy and freedom of speech?

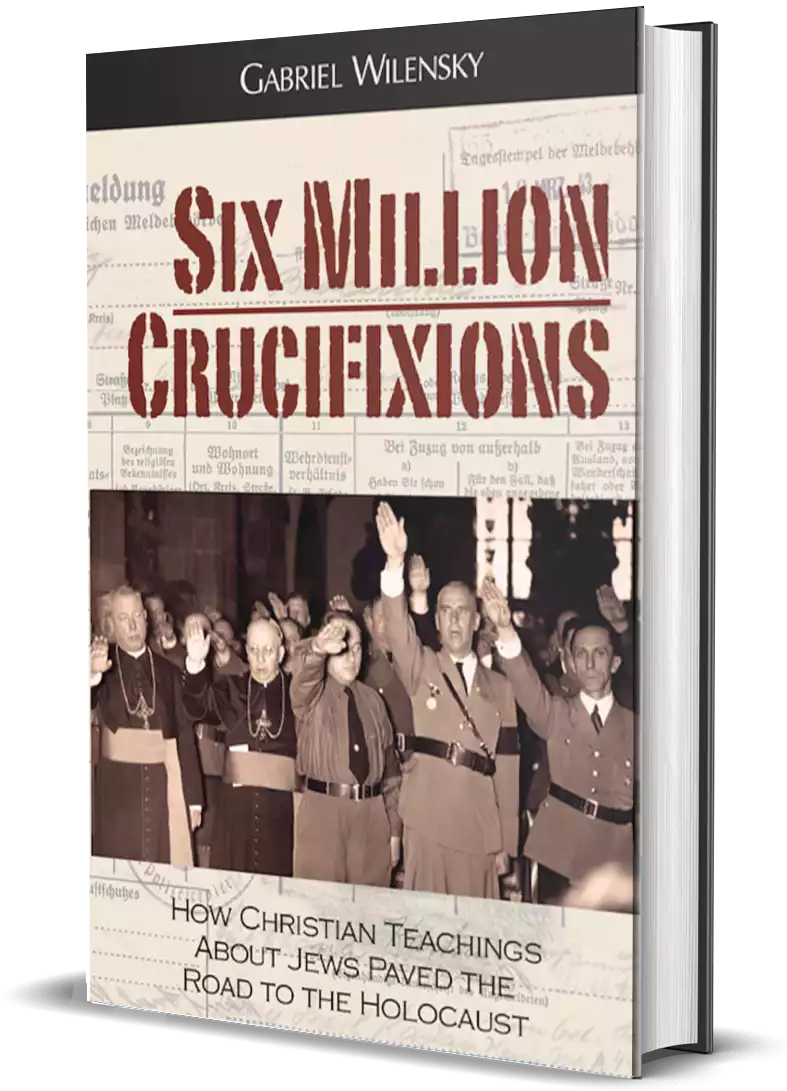

The Kulturkampf, the cultural struggle between Otto von Bismarck and the Catholic Church in the 1870s is a perfect example of what the church should have done vis-à-vis the Nazis as well. The Church opposed Bismarck, and the church eventually won, despite the many setbacks on the way. The church stood for what they believed was right in 1870. They could and should have kept the moral high ground and done the same thing against Hitler in 1933, even if that meant another struggle. The difference is that in 1870 Bismarck opposed the Catholic Church, while in 1933 Hitler opposed the Jews. On the second round the Church was not on the receiving end. Even though the Concordat was not intended to mean an endorsement or support of Nazi policies, that was actually the way the German Church and German Catholics widely perceived it to mean. The reason why they joined the Nazi party in droves was not just because the party was successful. They joined because they agreed with its ideals, and because once the Vatican signed the Concordat and the church lifted the ban German Catholics assumed that meant it was then all right to join, and that is precisely what they did.

“Even though the Concordat was not intended to mean an endorsement or support of Nazi policies, that was actually the way the German Church and German Catholics widely perceived it to mean. The reason why they joined the Nazi party in droves was not just because the party was successful. They joined because they agreed with its ideals, and because once the Vatican signed the Concordat and the church lifted the ban German Catholics assumed that meant it was then all right to join, and that is precisely what they did.”

Apologists for the church justify Vatican support for Nazi Germany in 1933 by claiming that in 1933 the majority of Germans supported the Nazis, and that fighting the Nazis would have been tantamount to suicide. Neither claim is true. The Catholic Center Party was very strong and in a coalition would have actually defeated the Nazis. We have Cardinal Pacelli to thank for the dissolution of the Catholic Center Party and for making Hitler’s absolute takeover of power possible. Even after Hitler came to power the strength and potential of the Church cannot and should not be underestimated. The Catholic Church prospered greatly under the Weimar Republic, increasing the number of priests to over 20,000 for 20 million Catholics, as opposed to sixteen thousand pastors for 40 million Protestants. Catholic organizations of every kind multiplied; new monasteries were built, new religious orders were founded, new schools were established. As the historian Karl Bachem said in 1931, “Never yet has a Catholic country possessed such a developed system of all conceivable Catholic associations as today’s Catholic Germany.” Some apologists for the church claim that the Concordat was signed not to protect church interests, but instead and in particular to protect the Jews. This is a preposterous claim. The Concordat was meant to protect church interests, not Jews.

Just as the Catholic Germans were supportive of the Church’s admonition to stay away from the Nazis before the ban was lifted, they would have remained that way if the Church had continued to keep the ban in place or at the very least advised the faithful clearly, repeatedly and in no uncertain terms that the Nazi ideology was evil and incompatible with Catholic teachings. By failing to do this the Church tacitly approved what was being done to the Jews.

It’s true that neither Cardinal Pacelli nor Pope Pius XI could have known what was coming, that they were making a pact with the devil (although they must have known Hitler and Nazi ideology were evil), that it would protect the church from the forthcoming Nazi terror (which in any case it didn’t and even then the church did not repudiate the pact), and even less, that it would help them protect all in need, especially the Jews. The latter claim never crossed their minds.

Cardinal Pacelli might have been concerned about excesses against Jews in Germany, and even discussed it. But actions speak louder than words, and he said very few words and acted even less. Pope Pius XI might have warned Mussolini that the racial laws might make him angry, perhaps even violently so. Yet, the racial laws stood, the pope never got past that and didn’t do anything about it other than complain about the treatment of Jews who had converted to Catholicism. The Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano may have declared that the church would defend the Jews, which of course surely looked good as it was later reported on the New York Times, but they had also declared at about the same time (June 1938) that the Jews “usurp the best positions in every field, and not always by legitimate means,” cause “the suffering of the immense majority of the native populations,” hate and struggle against the Christian religion, and favor Freemasons and other subversive groups. Father Rosa in the L’Osservatore Romano article called for “an equable and lasting solution to the formidable Jewish problem,” but counseled to do so through legal means. But this was no fluke, as there was a long history of antisemitism in this publication. Previously they had declared that “Antisemitism ought to be the natural, sober, thoughtful, Christian reaction against Jewish predominance” and, according to the paper, true antisemitism “is and can be in substance nothing other than Christianity, completed and perfected in Catholicism.”

Grab Your Copy Today!

Six Million Crucifixions

Traces the history of antisemitism in Christianity and the role that played in making possible the Holocaust.

Want to stay informed about the topic?

Subscribe below.